Before anyone gets me under the 'Goods Descriptions Act' (aka the 're-cycled Victorian' reference in this blog description) I thought it was about time I shared probably my favourite book in the world about Victorian times; an autobiography so vivid you are almost there; better still in relative middle-class comfort rather than as some Dickensian street sweeper or one of Mayhew's baby farmers.

Before anyone gets me under the 'Goods Descriptions Act' (aka the 're-cycled Victorian' reference in this blog description) I thought it was about time I shared probably my favourite book in the world about Victorian times; an autobiography so vivid you are almost there; better still in relative middle-class comfort rather than as some Dickensian street sweeper or one of Mayhew's baby farmers.A London Child of the 1870s is the entertaining and detailed chronicle of a young girl growing up with the benefit of four adoring elder brothers, detailing their everyday lives, the games they played, the dreams they dreamed and the harsh reality that often impinged, even on a family where good fortune shone rather than not. It is written by Molly Hughes, who went on to write the equally riveting 'A London Girl in the 1880s', 'A London Home in the 1890's' 'A London Family Between the Wars' as well as the semi-fictionalised 'Vivians' - the tragic mid-Victorian melodrama of her Cornish Aunt's doomed love affair with a Nordic sea captain - as dramatic as anything Daphne Du Maurier subsequently came up with. Molly Hughes herself was an early female University graduate and went on to become one of the first female school inspectors. One of Molly's observations was how; heroine or villain alike; most protagonists had to die at the end of a Victorian children's story to satisfy some Christian moral or other, and how she and her brothers would place bets on the outcome. Here is Molly's description of a typical Victorian children's story;

The Last Shop

A little girl who had a very rich mamma behaved herself so well one day that her kind parent said. 'Rosy dear, we will go for a walk down the street where the shops are, and you shall buy whatever you like, because you have been so good.' Skipping for joy little Rosy began to think of all the things she had been longing for. But mamma made one condition - that Rosy must buy something out of each shop. That seemed very easy, and the walk began well. A doll's perambulator in the first shop, some expensive lollipops in the next, some tarts at the confectioners, a pair of crimson slippers, some fancy coloured note-paper, a whole pineapple, and a real writing desk with some secret drawers in it. In each case the purchase was ordered to be 'sent' and Rosy soon became anxious to go home in order to be ready to receive them. But Mamma's face grew solemn.

'Have you quite finished, my child?'

'Oh, yes, thank you, dear mamma, pray let us return home'

'I fear, my child, that there is one shop that you have omitted.'

So saying, she led Rosy to the undertaker's, and had her measured for a coffin. In this way, my dear young readers, little Rosy was early led to realise that death was the necessary end to all her pleasures.

Talking of 'A London Child in the 1870s' reminds me of my other favourite autobiography, this time set in Edwardian times, 'People Who Say Goodbye' is the account of a precocious and cynical tomboy growing up in London's Wandsworth Common, the product of surprisingly liberal, progressive and loving parents. What is particularly striking is the bold humour and candour of this book - PY Betts had everyone around her weighed up it seems, and a startling ability to conjure the long-dead back to vivid life. Here is a passage from it;

Talking of 'A London Child in the 1870s' reminds me of my other favourite autobiography, this time set in Edwardian times, 'People Who Say Goodbye' is the account of a precocious and cynical tomboy growing up in London's Wandsworth Common, the product of surprisingly liberal, progressive and loving parents. What is particularly striking is the bold humour and candour of this book - PY Betts had everyone around her weighed up it seems, and a startling ability to conjure the long-dead back to vivid life. Here is a passage from it;'There was a big boy of eighteen, a young man really, ten years older than me, who lived in one of the houses on the other side of the Field. He had younger brothers and sisters, all older than me, whom I knew only slightly. His name was Tom. He was an art student but for how long I do not know. He was there in the glade and then later on he was not there any more, so very likely he went to the War and was killed. We would lie down in the bushes and he would cuddle me. He would look at me a long time and then ask if he could kiss me. I was not keen on being kissed so he took a Wolff's Lightning Eraser out of his pocket and said he would give it to me if I would kiss him. Being a stationery fetishist I found the India rubber irresistible and let him kiss me. The kiss did not affect me emotionally, all my desires were focussed on the rubber. We met in the hazel coppice several times. Each time he would cuddle me and ask to kiss me. I began to hold out for brand new Wolff's Lighting Erasers, spotless white ones with geometrically sharp corners. He never did anything but cuddle me, look at me, kiss me gently and hand out quantities of new India rubbers, wonderful for swapping at school or keeping and gloating over. It all ended without my noticing. Perhaps the art school got suspicious about the run on erasers, or perhaps Tom was called up and got killed, I did not notice when it ended. I had enough rubbers to be going on with. Their smell was so alluring, so satisfying.'

Both books are now sadly out of print, though probably available from second hand outlets.

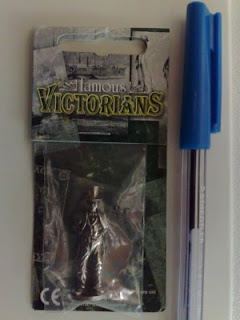

To hark back for a moment to Victorian times though, the other weekend I treated myself to our greatest Victorian engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel for £1.20 from Coventry museum - a man whose parents evidently didn't expect much when they christened him! He stands neatly in the palm of my hand. I wonder what he'd make of himself if he could see himself now embodied in miniature effigy form.

To hark back for a moment to Victorian times though, the other weekend I treated myself to our greatest Victorian engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel for £1.20 from Coventry museum - a man whose parents evidently didn't expect much when they christened him! He stands neatly in the palm of my hand. I wonder what he'd make of himself if he could see himself now embodied in miniature effigy form. I wonder what he would make of modern engineering and how the progress of our railways in particular has gone backwards since his time. I might play with him later.